CONTENT WARNING: This story features descriptions of child abuse and mentions the names of people who have died. Reader discretion is advised.

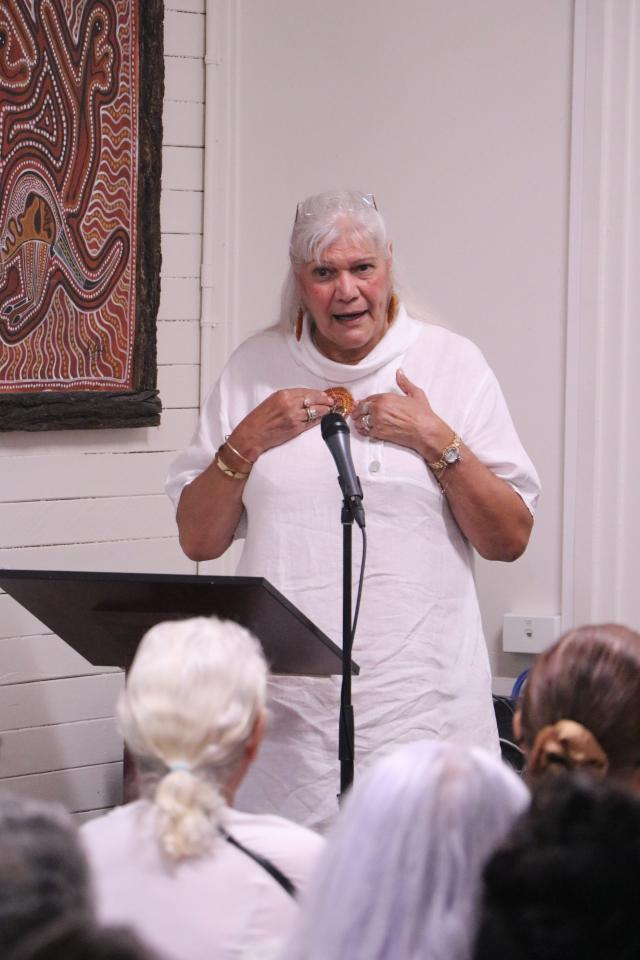

Andrea Collins PSM, daughter of the late Cherbourg elder Nan Eva Collins, spoke about her experience living in the Cherbourg Girls’ Dormitory during the launch of a new exhibition at the Ration Shed Museum on 2 October.

My grandmother told me that we were all brought here from other places. We are nations within a nation.

On my part, I’m a descendant of the Kuku Yalanji nation, of the Maranganji nation from my mother, and my grandmother was of the Koa nation.

Mum, Eva Collins nee Nixon, was brought here to the Dormitory at a very, very early age, in about 1932 when she was about nine.

Mum was in the Charleville Church of England home for her education. That year they took the kids to Redcliffe on an excursion.

When they were on that excursion, all of a sudden Mum was taken out of that group and brought in a car up here to be put in the Dormitory. She didn’t know anybody.

Can you imagine a child that age be put in the Dormitory here, knowing nobody?

When Mum was 13, that’s when her mother found out where she was. She demanded that Mum be taken out and brought back to where she was, back into her care.

Mum went, but she told me that when she went there to meet up with her mother there was no connection. She said ‘all that time, I thought that my mother had abandoned me.’

My mother lived with that all her years.

When the Apology [for the Stolen Generations] was announced by Prime Minister [Kevin] Rudd at the time, I said to her ‘Mum, that’s good ay? How do you feel now that the government’s made that announcement?’

She said ‘I wasn’t stolen! I was abandoned – my mother abandoned me.’

God help me, I had to talk Mum through it over and over again and tell her that she was not abandoned by her mother – she was taken, she was removed without her mother’s knowledge. It took years and years before Mum arrived at that acceptance.

Everything Mum did, she did with love. I think that’s because she felt that she missed out on the love from her mother.

She turned that into loving all of those girls, those single mothers, and all their babies.

When I was 11 I had to go into the girls’ dormitory. To spend time with my siblings, I was only allowed out once a month on a Saturday – and I had to get permission from the matron.

Even then, I wasn’t allowed out of the yard of my grandparents’ place.

We used to bathe and wash with kerosene soap. We had big slabs of it and would cut and shave it.

We never knew what a three-course meal was like; we never, ever knew.

We never knew what a salad was. I first heard about a salad when I was sent, at 14 years of age, to Roma to work for the Lewis’s, a doctor and his wife.

You’re still only a kid at that age, 14. I used to think to myself ‘I wonder what my mum would think’ because she was sent out to work too.

One day I asked her, I said ‘mum, you remember the time when I was sent out to work at Roma for the Lewis’s? Were you worried?’

She said ‘I was at first, but the thing that gave me consolation and comfort was knowing you were going to the Lewis’s – she was a nurse at the Cherbourg hospital.’

I can remember come wintertime, we only had our fibre mattresses and a sheet with one blanket. We used to pull the string off the edge of the blankets to knit with; we’d bend nails and knit with the cotton off the blankets.

When it was freezing, we’d push two beds together, get the blanket off the other bed, and four or six of us would cram into those beds. Even that was not enough.

We’d have to take the mattresses off the other beds and put them on top of us to keep us warm.

I always thought about the occupational health and safety of that place.

We were all upstairs at nighttime, and while the downstairs had a cement floor everything else was polished [wooden] floors.

We were washing the verandahs every day, and on Saturdays we had to get on our hands and knees to scrub them – patch by patch. I can only imagine how thin those floorboards would have been.

If a fire would have broken out downstairs, it would have been a disaster.

When we were there there were four fire escapes. Those fire escapes were caged in with wire.

I can just visualise it: if a fire would have broken out, and we tried to get through, there would have been no way in the world.

My experience in the dormitories has made me so resilient, so strong.

In my two marriages, I fought those men like a man. I had to stand up and physically protect myself.

I just walked away; God didn’t make me for this, God had me for a purpose. I want to live my life for that purpose.